Leaf blowers, industrial culture, and the Great I Am (part 1)

This is one of four seasonal posts that reflect my struggles to live with integrity in a society built on consumerism, industrialism, and systemic oppression. How can I reconcile my desire to change the world and my desire to accept the world as it is? Doubts and dilemmas run through all four posts, and I describe tripping over myself (in ways that are typical of someone who leads with a One in the Enneagram). I also mark times when Spirit uplifts me and turns me around unexpectedly, times when I am more aware of God’s expansive presence within me.

- Spring: Easter egg hunts, consumerism, materialism, and acceptance

- Summer: swimming pools, landfills, and environmental racism

- Fall: leaf blowers, industrial culture, principles, and humility

- Winter: lighted Christmas balls, appreciating the natural world, and living in a neighborhood

Autumn is here. It’s time for cool mornings, apples, falling leaves… and the sweet sound of leaf blowers.

Leaf blowers epitomize the worst of Western Civilization. At least that’s what I used to think. One day in 2018 I returned home from a walk in my neighborhood enraged by the noise of leaf blowers. I sat down and began writing Part 1 of this post, a lecture by an angry anthropologist. Then last year I faced a dilemma that changed my perspective. I tell that story, which took a surprisingly spiritual twist, in Part 2.

I can only awkwardly stitch these two parts (two genres, two versions of me) together. I still see some truth in what I wrote in 2018, but I also recognize black-and-white thinking and extreme conclusions. I can’t get rid of the awkwardness because underneath my evolving thoughts about leaf blowers lie changes in me that don’t erase what came before. There is change and there is continuity. Welcome to the awkwardness of my personal growth!

First, the lecture…

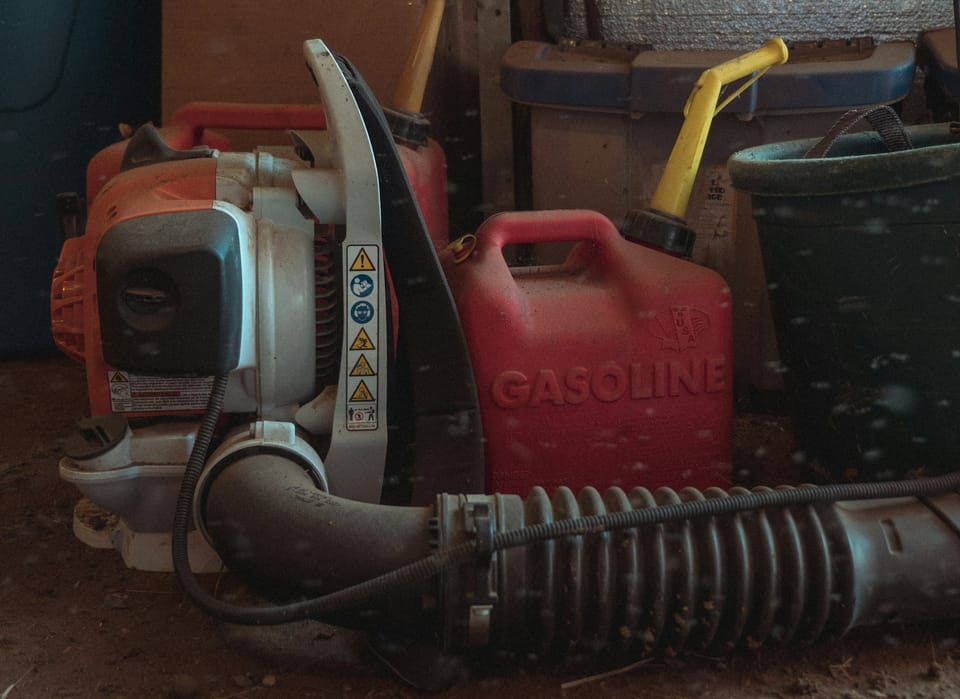

Leaf blowers perfectly embody industrial culture. Perhaps that’s why they’re ubiquitous: not because they are effective tools but because they express our dominant values so powerfully.

Here’s a machine that fulfills our desire to dominate and control nature. We want the natural world to be orderly, not wild. Fallen leaves spoil lawns that we think should be clear and clean. Leaves are waste, so we send them away.

A single misplaced leaf can offend bourgeois sensibility. I have seen people painstakingly blowing yards that are virtually leafless, waging war on individual leaves with their big machines. This is often a border war: get your leaves off my property. One homeowner in our neighborhood erects a temporary fence each fall between his yard and his neighbor’s to keep his neighbor’s leaves from crossing the line. The task is usually Sisyphean. I have watched, perplexed, as people blow leaves into busy streets. Cars zoom by and the leaves swirl in the air, landing right back where they started.

Rakes and brooms can also be used to reorder the world, but leaf blowers accomplish the task more powerfully, quickly, and (we think) efficiently. Power, speed, and efficiency: what an enticing combination. Our industrial systems, from food systems to transportation to education, are built around these values.

Leaf blowers satisfy our love of power. Donning these powerful machines make us supermen. (I mostly see men using leaf blowers, which isn’t surprising, since men in our society are taught to work outside and to love power and domination.) Long before the invention of leaf blowers Sigmund Freud argued in Civilization and Its Discontents that with every new tool humans perfect their organs (with “perfection” culturally defined). With auxiliary organs we become “prosthetic gods.” Or, as David Dudley puts it, wielding a leaf blower is “akin to being some kind of ancient wind deity.”

The flip side of this prosthetic power is the general devaluation of physical labor in our dominant culture. Less work (meaning bodily effort) automatically appears better than more work. Simultaneously, industrial culture devalues workers themselves, especially manual laborers. Middle class white men in suburbia may gear up to perform their manly outdoor duties on the weekend, but most of the leaf blowing in our country is carried out by low-wage workers. These workers are exposed to hazardous fumes, fine particulates, and dangerous noise levels. Industrial capitalism deprioritizes the health and well-being of workers in general, and that’s even more true for immigrants and people of color, who fill out many landscaping crews. Their machines may be powerful, but they are not.

When it comes to efficiency, leaf blowers may appear objectively superior to rakes, but that depends on how you measure efficiency. Producing a leaf blower takes more energy and material than producing a rake or broom. The leaf blower then requires gas or electricity every time it is used. The production of this energy itself requires huge investments in extraction, processing, and infrastructure. The two-stroke engines in most gasoline powered, backpack-style leaf blowers are so inefficient that they’ve been banned from vehicles in the developing world. The environmental impact of gas-powered leaf blowers is staggering (Environment America Research & Policy Center, Bloomberg, Washington Post). Like so many parts of industrial society, the true costs of leaf blowers are hidden and externalized. By contrast, rakes and brooms soar in their simple efficiency.

Finally, there’s the noise—the most reviled feature of these machines and the primary reason for the “leaf blower wars” erupting in municipalities (see James Fallows’ series “The Leafblower Menace”). The people wielding leaf blowers often seem unaware (or unconcerned) that the noise they produce might bother other people. They do not seem to perceive the noise as a problem, perhaps because it is an accepted consequence of “development” or industrial modernity. Even more troubling is the possibility that they may like the loudness of their machines. Imposing our sounds on our neighbors indulges our love of individualism, assertiveness, and aggression. Leaf blowers (like loud music and motorcycles) are “aggressively un-civil” (Dudley).

The culture of leaf blowers is therefore a culture of domination, disregard, and aggression.

What kind of culture would endorse the rake instead? It would be one that values quiet, slowness, simplicity, neighborliness, self-restraint, a more intimate connection to the non-human world, the pleasure and honor of physical labor. It would not tolerate bothersome noise and emissions that threaten human health and life on the planet.

What if we let go of our constant need to domesticate the natural world and demonstrate our dominance? What if we stopped thinking of leaves as waste and started thinking of them as resources? “Leave the leaves” movements are catching on around the country as cities and homeowners reclaim the value of fallen leaves. In forests, after all, there is no waste, just the perpetual recycling of nutrients. What if we modeled our yards not on aristocratic British estates but on forests, prairies, deserts, or wetlands? I’ve taken small steps in that direction, replacing all my grass with beds mulched with leaves. I’m delighted to see many neighbors doing the same.