The landfill and the swimming pool (part 1)

This is one of four seasonal posts that reflect my struggles to live with integrity in a society built on consumerism, industrialism, and systemic oppression. How can I reconcile my desire to change the world and my desire to accept the world as it is? Doubts and dilemmas run through all four posts, and I describe tripping over myself (in ways that are typical of someone who leads with a One in the Enneagram). I also mark times when Spirit uplifts me and turns me around unexpectedly, times when I am more aware of God’s expansive presence within me.

- Spring: Easter egg hunts, consumerism, materialism, and acceptance

- Summer: swimming pools, landfills, and environmental racism

- Fall: leaf blowers, industrial culture, principles, and humility

- Winter: lighted Christmas balls, appreciating the natural world, and living in a neighborhood

Environmental racism has two sides. Environmental hazards (such as industries and infrastructure that pollute or produce toxic substances) are disproportionately located in communities of color. And environmental goods (such as access to fresh food, spaces for outdoor recreation, and clean air, water, and soil) are disproportionately located in white communities. (If you’re unfamiliar with environmental racism, here’s an introduction.)

These are two sides of the same coin. The presence of environmental dangers in Black and brown neighborhoods relates to their absence in white neighborhoods. Conversely, the presence of environmental amenities in white neighborhoods relates to their absence in Black and brown neighborhoods. Although this doesn’t have to be a zero-sum game, it often is.

Lately I’ve been thinking about two holes in the ground that illustrate the two sides of environmental racism in Greensboro, North Carolina, where I live. Last year a controversy erupted over the city’s repeated failure to clean up the site of a former landfill in a predominantly African American neighborhood in eastern Greensboro. Meanwhile, across town, my white family wrestled with whether to join a private swimming pool, knowing that the abundance of private pools in white neighborhoods and the paucity of public pools throughout the city is a product of racism.

In this post I recount the histories of the landfill and the swimming pool and my struggle to discern what I could or should do about them. I believe in environmental justice (an equitable distribution of environmental hazards and goods), and I want to work for it. But how? Environmental racism is rooted in complex systems and structures. It’s not always obvious (at least to me) how to intervene.

Many discussions of environmental racism and many environmental justice campaigns focus on communities of color, which have too many environmental hazards and too few environmental resources. Environmental racism often appears to be a problem for people of color and for policy makers. But what if it is a problem for affluent white people like me too? In The Sum of Us, Heather McGhee argues that the zero-sum paradigm of race relations (where every advantage for one group comes with a disadvantage for another) is a lie created by the wealthy and powerful (xxii). The truth is that what’s good for one group tends to be good for everyone, and what’s bad for one group tends to be bad for everyone. Good things and bad things tend to cross social borders.

I believe that there’s important environmental justice work to do in affluent white neighborhoods like mine (Sunset Hills). At the end of Part 2 of this post I outline some potential action steps for myself, and I invite other well-off white people concerned about environmental racism to join me. Although I’m writing about Greensboro, similar patterns are found across the United States.

The landfill

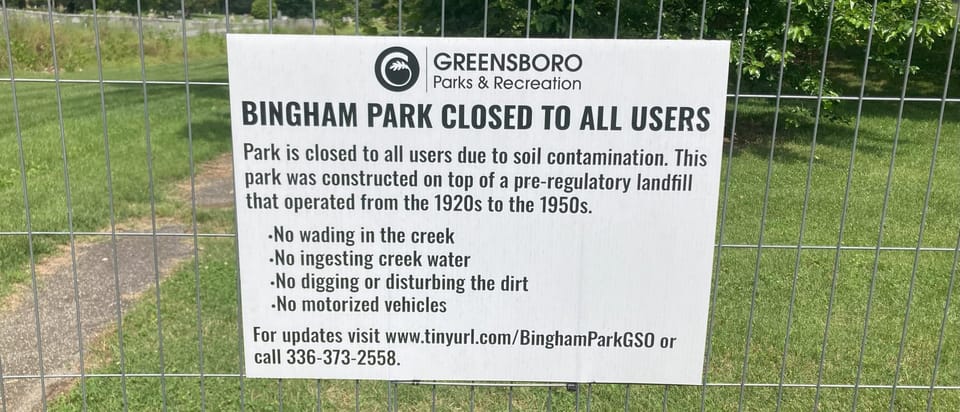

I first heard about Bingham Park in early 2024 thanks our local newspaper, the News and Record. But the problems associated with it go way back.

Bingham Park sits in eastern Greensboro, which the city and developers have ignored and exploited for more than a century. In the 1920s the city opened an unlined landfill at the site, despite protests from nearby residents, and began incinerating and burying waste from households and the U.S. military there. The landfill was closed and covered with soil in the 1950s, but by then the site was contaminated with lead, arsenic, iron, manganese and other toxic substances. The city opened Bingham Park on top of the former landfill in the 1970s. In 2022 the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality conducted testing at the site and warned people against drinking water from the stream that runs through it, digging in the soil, or consuming soil. In April 2024 the city closed the park altogether after the EPA updated guidelines on acceptable levels of lead exposure. The adverse health effects of living near landfills and other environmental hazards are well documented, including in Greensboro (see this article and this op-ed).

In 2024 the city began exploring two options for remediation: relocating 12,000 truckloads of contaminated soil to a properly lined landfill (full remediation) or leaving the soil in place and capping it with a fabric covering topped with more soil. Three destination landfills were considered for full remediation: Greensboro’s White Street Landfill and two landfills outside the city. The White Street option initially appealed to the City Council because it would be quicker and cheaper than the other two, but residents protested vigorously. The city closed the White Street Landfill to all waste except construction debris and yard waste twenty years ago after a protracted environmental justice campaign. Residents pointed out that the White Street option pitted two Black communities against each other. When officials suggested that the city could offer amenities such as sidewalks to the neighborhood around the White Street Landfill to compensate for relocating the toxic soil there, residents understandably took offense, arguing that they should have had those amenities years ago.

The city’s Parks and Recreation Commission, the Bingham Park Environmental Justice Team, and community members all recommended full remediation. But in October 2024 the Council voted to cap and cover the site, saying full remediation was too expensive. This will leave all the contaminated soil in place and severely limit the use of the park in the future. Nothing that could puncture the fabric covering will be allowed: no trees, paved paths, basketball courts, ball fields, or structures. The city is currently reviewing proposals for partial remediation (here’s the city’s Bingham Park web page).

This is a history of ongoing injustice and moral failure. The production, incineration, and disposal of toxic material was wrong in the first place (even if people didn’t know it at the time). The opening of the landfill in a disadvantaged community in the 1920s was wrong. The lack of environmental safety precautions was wrong. The cover up of the site, without remediation, in the 1970s was wrong. The city’s refusal to fully remediate the site in 2024 was wrong.

The city should right these wrongs, once and for all. It’s true: full remediation would cost a lot of money. But “the city” is more than its government, and its resources are abundant. In response to the Bingham decision, Allen Johnson, the Executive Editorial Page Editor of the News and Record, pointed out that the city raised more than $42 million in private funds for the downtown Tanger Center for the Performing Arts, invested nearly $19 million in the Greensboro Aquatic Center, and spent $25 million in bonds for downtown landscaping. Johnson criticized the City Council for its lack of ambition and imagination in finding other funding partners.

I believe that affluent white neighborhoods like mine also bear some responsibility to right this wrong. We have benefited over the last century from the fact that waste (including our own waste) was sent to someone else’s neighborhood, to pollute their soil and water and bodies. The benefit comes in the form of relative freedom from exposure to environmental danger. This benefit is immeasurable. How can people in protected neighborhoods like mine fathom the blessing of lower rates of asthma, cancer, cognitive impairments, and other environmental ailments? We likely take them for granted as normal. But they come at the cost of sickness and death in someone else’s neighborhood.

Nagatha Tonkins expressed our interconnectedness beautifully in a letter to the editor: “You may say Bingham Park isn’t my problem; it’s not in my neighborhood. Well, it’s not in mine, either. However, as a Christian, it is my problem. Galatians 6:2 says, ‘Bear one another’s burdens, and in this way you will fulfill the law of Christ.’ If our brothers and sisters are hurting, we should hurt, too. Everyone should be disappointed and outraged!”

Freedom from environmental harm combines with countless other benefits that have accrued to white communities. Neighborhoods like mine have substantial financial resources that have accumulated over generations. We can afford to pay part of the costs of righting historic wrongs in our city.

When I read that the City Council rejected full remediation, I finally decided to do something. I called one of the two council members who voted against the city plan and shared with him my sense that the city (broadly conceived) had plenty of resources to cover full remediation and that wealthy, white neighborhoods could be organized to help right this wrong. He was receptive, and we discussed the possibility of a meeting with the city manager to explore options. But then the November 2024 election hit, and in early December the other council member who voted against the city plan (a longtime and beloved Greensboro leader) died. So I never heard anything more. The last time I checked in with the council member, he said full remediation “would be challenging and expensive at this point.” In June of 2025 I attended a statewide environmental justice gathering in Greensboro and met two people who are still fighting for full remediation. I plan to support their efforts.

While I was motivated by my sense of injustice and my vision of shared responsibility, holding me back were my lack of knowledge about a complicated issue and a sense of guilt that I should have done more sooner. I should have been better informed. I should have been building relationships with community members and environmental justice activists across Greensboro. I was wary of white saviorism. By the time I finally took action, it was too little, too late.

I’m writing this partly to confess and move past my own hang-ups. At the end of Part 2 of this post I’ll outline a few ways I’m hoping to overcome uncertainty and guilt when it comes to confronting environmental injustice.